Everyone knows Michael Burry for one thing:

He is the guy who shorted the housing market and made $100 million while the world burned. The guy who got played by Christian Bale in The Big Short.

But there is way more to know about him.

Before the fame, before the movie, before the trade that made him one of Wall Street’s most famous investors, Burry was a doctor.

A medical resident at Stanford, studying neurology by day and reading 10-Ks by night. He shared his stock ideas on early internet forums and wrote in-depth research on his blog, quietly outperforming the market with his personal portfolio.

His work was so compelling that it caught the attention of Joel Greenblatt, one of the most respected value investors of all time. Greenblatt didn’t just like Burry’s ideas, he gave him $1 million to support his hedge fund.

In 2000, he launched Scion Capital.

By 2004, he was managing $600 million.

Long before anyone cared about subprime debt, Burry was already crushing the market with deep-value picks, net-nets, and obscure microcaps most investors wouldn’t even touch. He was a relentless deep-value investor with a clear strategy, an independent process, and an obsession with downside protection.

To say the least: it worked.

This write-up isn’t about the Big Short.

It’s about everything that came before it.

About the real strategy behind the returns, what he looked for, how he thought about value, how he picked stocks, valued them, managed risk, and built a portfolio that could actually beat the market.

Let’s break it all down.

Investing Style

Michael Burry’s investment philosophy is deeply rooted in classic value investing. He draws heavily from the principles outlined by Benjamin Graham in his book “Security Analysis”.

Of course, Michael Burry went and put his own spin on his ideas.

„As my moniker implies, I’m a value investor. A pretty deep one. Yet while my influences are traditional, I’ve developed my own version of value investing. This version has been tuned empirically with a singular goal: maximize risk-adjusted returns“

In essence he looks for companies trading below their intrinsic value.

Often focusing on distressed or misunderstood companies that the market overlooks. Stocks that look like “roadkill,” as he puts it—until they don’t.

„My strategy isn’t very complex. I try to buy shares of unpopular companies when they look like road kill, and sell them when they’ve been polished up a bit.“

Let’s start unpacking his strategy with the one thing that drives it all:

What He Looks For

One thing that became clear to me when studying Michael Burry’s work is this: The number one thing he looks for is Value.

Uncovered, overlooked and mispriced value.

It‘s not important to him where he finds it. Whether it’s in a growth stock or a microcap, a popular tech name or an obscure industrial, even land or water rights.

If Burry can find value in it, it becomes a candidate for his portfolio.

Interestingly, he is not looking for specific, known catalysts (an event which causes investors to finally recognize a stock’s true intrinsic value and causes the stock’s price to “pop”) before he makes an investment.

Sheer value is enough.

That’s where the market efficiency theory comes into play.

If the gap between price and intrinsic value is wide enough, the market will eventually catch on. And price will correct itself, returning to fairvalue.

Value itself becomes the catalyst.

Michael burry likes to fish where nobody else is looking. That‘s where he finds overlooked opportunities.

„I have found, however, that in general the market delights in throwing babies out with the bathwater. So I find out-of-favor industries a particularly fertile ground for best-of-breed shares at steep discounts“

Burry doesn’t restrict himself to certain sectors or company sizes. And yet, the majority of his ideas end up being small, illiquid microcaps.

Simply because of their nature: because they are so overlooked by Wall Street, that’s where a lot of mispricing occurs. Therefore inefficiencies tend to be more extreme.

“I go where I can find the most value. Currently, that happens to be in small caps and illiquid securities“

Still, he doesn’t limit himself. He said he has a list of 80 large-cap stocks he’d love to own. If the prices were good.

„The prices at which I’d love to own them are so much lower than today’s prices it would make you laugh.”

His write-ups on Value-investor-club (VIC) are perfect to showcase how he favors small and illiquid microcaps.

These are the companies he wrote about and their marketcap at that time:

Huttig Building Products (HBP): $90M

ValueClick, Inc. (VCLK): $125M

GTSI Corp (GTSI): $40M

Quipp, Inc. (QUIP): $38M

Wellsford Real Properties (WRP): $139M

Pillowtex (PWTX): $64M

Industrias Bachoco (IBA): $426M

Average marketcap: $131M

Sidenote: If you’re unfamiliar, Value Investors Club is a members-only forum for deep-value write-ups, founded by Joel Greenblatt. Burry used to publish some write ups there in the early 2000’s. You can read them here. Also I still think its a great place to find investment ideas, I can recommend it a lot.

Here is another interesting detail from those write-ups:

Almost every company he pitched had a relatively low sharecount.

Huttig Building Products (HBP): ~21M

ValueClick, Inc. (VCLK): ~28M

GTSI Corp (GTSI): ~8M

Quipp, Inc. (QUIP): ~2M

Wellsford Real Properties (WRP): ~8M

Pillowtex (PWTX): ~20M

Industrias Bachoco (IBA): ~50M

Except for IBA, Burry’s companies averaged a share count of ~14.5M shares.

Even though he never explicitly mentioned it, looking at the sharecount of the stocks he wrote about it looks like he values it. And there are good reasons why:

Less dilution risk: Fewer shares means less room for dilution through secondary offerings.

Better alignment: Management is less likely to treat their stock like “cheap currency” when shares are scarce. Meaning they are not using them to overpay for acquisitions or pay employees, which can dilute the value of existing shareholders’ holdings.

Illiquidity premium: Illiquid stocks are often ignored by institutions, creating opportunities for those willing to do the research.

Burry also talked about so-called “rare birds”:

„I also invest in rare birds — asset plays and, to a lesser extent, arbitrage opportunities and companies selling at less than two-thirds of net value (net working capital less liabilities). I’ll happily mix in the types of companies favored by Warren Buffett — those with a sustainable competitive advantage, as demonstrated by longstanding and stable high returns on invested capital — if they become available at good prices.“

The last bit is very important.

Unlike Buffet, Burry isn’t focused on wide moats or durable advantages. That statement highlights again his almost obsessive focus on sheer value and mispricing.

He is after dollars selling for 50 cents, regardless of how glamorous the company is.

Now that we know what Burry focuses on, let’s now look at how Burry actually goes about finding and valuing those opportunities.

How he Finds and Values Stocks

Unlike many of his peers on Wall Street, Michael Burry doesn’t rely on tips, sell-side research, or other people's models.

He likes to find his own ideas.

“I think a lot of hedge funds get their trades from Wall Street and get their ideas from Wall Street. And I just like to find my own ideas. I’m reading a lot; I read a lot of news. I’m addicted to it. I basically – I follow my nose on news stories.”

Investors who actively seek their own opportunities may discover insights that elude those who rely solely on mainstream sources.

This gives him an edge.

Burry’s entire edge is built on finding value where others haven’t looked. I mean that’s exactly how he uncovered the housing bubble in 2005.

You don’t uncover those kinds of opportunities by watching CNBC. You find them through research.

„My weapon of choice as a stock picker is research“

So, how does Burry actually find value?

It starts with screening.

He uses stock screeners to sift through thousands of companies based on simple metrics. Chief among them: EV/EBITDA (acceptable ratios for Burry vary with the industry and its current position in the economic cycle, likely though something below 10).

He prefers enterprise value over market cap, since EV includes debt and gives a clearer picture of a company’s valuation.

If a stock passes his loose screen, Burry then looks harder to determine a more specific price and value for the company. This involves looking at true free cash flow and taking into account off-balance sheet items.

He avoids metrics like P/E and ROE, which he considers misleading. He also prefers companies with minimal debt and adjusts book value to reflect a more realistic picture.

Cash flow, in particular, is a key focus.

Free cash flow is a critical indicator of a company’s financial health, representing the cash a company generates after accounting for cash outflows to support operations and maintain capital assets.

Burry focuses on companies generating positive and growing free cash flow, suggesting they have more flexibility for debt repayment, dividends, and reinvestment in growth opportunities.

When evaluating Pixar in the early 2000s, Burry wrote:

„Pixar is generating cash at such a rate that it is building its new Emeryville digs out of cash flow—with no financing—and still laying down cash on the balance sheet. At present, cash on hand tops $214 million...

Whatever the reason, I like cash too.”

Lest you missed it, let me highlight Dr. Burry’s final statement, as it sheds pertinent light onto his personality:

„Whatever the reason, I like cash too.“

Another key factor of Burry’s process is understanding the business model.

Not just the numbers, but the actual mechanics of how the company makes money, and whether it can keep doing so.

„It’s critical for me to understand a company’s value before laying down a dime.”

That edge often lies in misunderstanding.

When other investors don’t get the business, the stock price can fall far below its intrinsic value. That’s where Burry looks.

„And where there is misunderstanding, there is often value.“

This obsessive research ethic was clear even before he launched Scion Capital. As a medical resident, Burry posted long, detailed write-ups on his blog valuestocks.net. He later recalled:

„Even with my time constraints, I came to realize that I had researched the companies about 10 times more thoroughly than any of the analysts I interviewed.“

Finally, and maybe most importantly, Burry focuses on absolute cheapness, not relative cheapness.

Buying absolutely cheap stocks means you don’t care about relative valuations. You assess each stock on its own merit. The only yardstick for “cheapness” is the price you’re willing to pay to generate your desired rate of return.

This is important because the market often over-values companies or entire industries. Investors buying relatively cheap stocks will automatically pay higher prices. A company trading at 20x earnings looks relatively cheap if the rest of the industry trades at 30x.

Absolute cheapness protects investors from falling into such traps.

Here is an example from Burry’s write-ups:

Industrias Bachoco (IBA) was Mexico’s leading poultry producer, with best-in-class margins and ROE. Yet it traded at 2x ex-cash earnings and 0.5x book vlaue, while peers traded 3-5x higher. But it didn’t matter because IBA was absolutely cheap.

Net-nets, stocks trading below liquidation value, are another great example.

These are companies the market values “more dead than alive”. And while investable net-nets are rare, I like them a lot. If you buy something below liquidation value, the downside is limited by definition.

But finding a good stock is far from everything.

„A portfolio manager must understand that safeguarding against loss does not end with finding the perfect security at the perfect price. If it did, then the perfect portfolio would likely consist of one security“

In other words: research is the foundation, but without risk management it doesn’t matter much.

Let’s look at how Burry thinks about portfolio construction.

Portfolio & Risk Management

Portfolio management and risk management go hand in hand. And if there’s one thing Michael Burry emphasizes consistently, it’s downside protection.

“Lost dollars are simply harder to replace than gained dollars are to lose.”

Protecting capital comes first. Stock picking matters, but managing the portfolio well is just as important:

„Management of my portfolio as a whole is just as important to me as stock picking, and if I can do both well, I know I’ll be successful.“

Naturally, that raises a few key questions:

What is the optimum number of stocks to hold? When to buy? When to sell? Should one pay attention to diversification among industries and cyclicals vs. non-cyclicals? How much should one let tax implications affect investment decision-making? Is low turnover a goal?

Burry says that in large part, the answers to these questions are “a skill and personality issue, so there is no need to make excuses if one’s choice differs from the general view of what is proper.”

But here’s what worked for him:

How many stocks?

“I like to hold 12 to 18 stocks diversified among various depressed industries, and tend to be fully invested. This number seems to provide enough room for my best ideas while smoothing out volatility, not that I feel volatility in any way is related to risk.“

This aligns well with Buffett’s view that holding too many stocks just dilutes performance. If you know what you’re doing!

Diversification makes sense for defensive investors. But Burry protected his downside not with broad exposure, but by buying cheap, with a fat margin of safety.

When to buy?

“As for when to buy, I mix some barebones technical analysis into my strategy — a tool held over from my days as a commodities trader. Nothing fancy. But I prefer to buy within 10% to 15% of a 52-week low that has shown itself to offer some price support.“

When to sell?

“Tax implications are not a primary concern of mine. I know my portfolio turnover will generally exceed 50% annually (…) So I am not afraid to sell when a stock has a quick 40% to 50% pop.”

“And if a stock breaks to a new low, in most cases I cut the loss. That’s the practical part. I balance the fact that I am fundamentally turning my back on potentially greater value with the fact that since implementing this rule I haven’t had a single misfortune blow up my entire portfolio.”

This focus on downside protection also comes to shine when looking at his write ups on VIC.

Take ValueClick (VCLK), for example, Burry starts the write-up discussing downside protection:

“[Here’s an] Internet asset play trading below cash and equivalents, with no debt and with an expectation of positive operating earnings by the end of the next fiscal first quarter.”

Notice how Burry initially outlines the downside protection (“asset play trading below cash”) and then provides reasons why the stock should inflect higher (“expectation of positive operating earnings by the end of next fiscal first quarter”).

GTSI is another example of Burry’s obsession with downside protection. Here’s how he started his write-up:

“[GTSI is] a debt-free net-net stock, now showing earnings growth and consistency for the first time.”

And again in his WRP write-up from June 2001. Here’s how he starts the thesis:

“WRP is an opportunity to buy real estate at as little as 50 cents on the dollar (and at most 61 cents on the dollar), with a plan for value realization in place and virtually no downside.”

Notice the last part … “And virtually no downside.”

Burry knows that one awful year could ruin a lifetime outperformance. Therefore the key to outperformance is not losing money. He says something like this in one of his investor letters:

“Any alpha that this fund generates will be the result of our obsession with reducing our downside risks.”

And when the thesis breaks, he cuts his loss.

A great example is Alliance Semiconductor corporation (ALSC), which he invested in and wrote about in July 2000.

After the stock broke its 52 week low. He got out and stated:

„ALSC tripped my sell point - I'm out already. It may go up, but I've vowed never again to cling to a falling knife. There are plenty of other opportunities out there.”

Which perfectly showcases his ability to cut losers and manage risk.

Funny enough after he got out the stock fell another 70%.

Hedging (Or Why He Rarely Does It)

Hedging is another topic for burry.

Despite running a hedge fund, Burry wasn’t a fan of hedging. In fact, he once called Scion an „unhedged hedge fund“.

He stated that he doesn’t see the need for hedging, by buing an appropriately safe and cheap stock.

In his first letter to investors in January 2001, just two months after starting the fund, he wrote:

“Common hedging techniques include shorting stocks, buying put options, writing call options, and various types of leverage and paired transactions. While I do reserve the right to use these tools if and when appropriate, my firm opinion is that the best hedge is buying an appropriately safe and cheap stock. (…) the charter investors in the Fund -myself included- entered November in a hedge fund that was, by all convention, completely un-hedge.”

He stated that he will only use shorting when he believes a stock is overvalued and he sees an opportunity, not as a riskmanagment tool.

“I Short a stock for the Fund when there is some temporary, manipulated, or misunderstood phenomenon that has caused the stock to rise to an egregious valuation.”

Even John C. Bogle, the founder of the Vanguard Group, one of the world’s most famous investors poked fun at his strategy:

“His technique to manage risk is to buy on the cheap and, if he takes a short position – I hope you’re all siting down for this – it is because he believes the stock will decline”.

Aligning Incentives (Fund Structure & Fees)

This isn’t about portfolio management anymore, but what I also found interesting about Burry and the way he ran his fund were the management fees.

Most hedge funds charge 1 & 20 or 2 & 20.

Which means a fixed annually fee plus 20% of profits.

This leaves the classic problem of „tails we win, heads you lose“

Burry criticized the industry for rewarding salesmanship over skill. Managers could raise massive capital, lock it up for years, and earn fortunes without actually being good investors.

So he did it differently.

He did not charge any management fees.

In order to keep the expense ratio low, he only charged for the fund’s running costs, always under one percent. It had a success fee of 20% subject to conditions – only when the Fund’s annual performance return exceeded 6% did the company take its 20% fee.

“I do not earn an income unless your annual return exceeds 6% net of expenses (…) my financial incentive to have an income give me every reason to rationalize expenses in favor of return.”

And to prove alignment, Burry had one rule:

“As long as the Fund exists, it will be my only investment.”

No side bets. No other holdings. Just Scion.

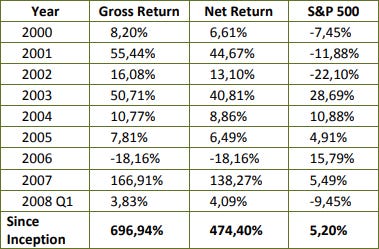

Scion Value Fund lifetime returns:

Final Thoughts

Burry is often remembered for one trade. But if you’ve made it this far, you know there’s much more to the story.

He didn’t stumble into success by accident. He built his edge from the ground up. Rooted in deep research, pure value, and an obsession with protecting the downside.

And most importantly, he shaped his style to fit who he was. He didn’t copy Buffett. He didn’t try to mimic Wall Street. He just followed the numbers, quietly and relentlessly.

“If you are going to be a great investor, you have to fit the style to who you are.”

That might just be the lesson here. There’s no perfect formula.

Burry’s approach is a great reminder that consistency, clarity, and conviction can go a long way, especially when paired with humility:

“I do not view fundamental analysis as infallible. Rather, I see it as a way of putting the odds on my side… I might even make an error. Hey, I admit it. But I don’t let it kill my returns. I’m just not that stubborn.”

At the end of the day, investing isn’t pure science. And it’s not pure art either. As Burry put it:

“In the end, investing is neither science nor art — it is a scientific art.”

And if done right, it can lead to something far more rewarding than just returns.

I learned a lot from Burry.

Especially: my love of roadkill stocks, and my ev/ebit screening

https://open.substack.com/pub/benevolusinsights/p/my-investing-philosophy?r=252ibd&utm_medium=ios

I think you misread the share count thing. A small share count is just the result of a small market cap, combined with not wanting to be a penny stock.